Art Blog

This blog is for posting photos of new art pieces and the random thoughts of oil painter Stephen St. Claire.

Regarding Commissioning a Painting

I received a super nice email from a potential client a week or so ago. They'd visited my art studio / gallery in Asheville's River Arts District and liked my work. It sounded like they were looking for a specific size but didn't really want to commission something. They wrote:

"I am a bit hesitant at the idea of a commission, because I want the artwork to reflect your vision, not mine."

That struck me in two ways. First of all, it's over-the-top respectful, so bravo possible future client! You won me over! But second, it sort of implies an assumption about how I work: "If the subject matter for the painting comes spontaneously from the artist's head and heart, it will give the artist more joy and the end result will be a better painting." I'm not familiar with the way other artists work and their motivation behind everything they do, so maybe that assumption is accurate for some people, but it is not at all descriptive of me. So I responded:

"I understand and appreciate what you said about commissions, but honestly, commissions and artists have gone hand-in-hand for centuries (over half of what I paint are commissions). I just really love painting, and I am immersed and emotionally invested into every piece. In other words, it’s not like I give my all to some idea I choose and give half-hearted attention to an idea someone else chooses. In fact, some of the most challenging and exciting paintings I’ve ever done were commissioned by a client. I love every project I assign myself or is assigned to me. I just really like creating."

Every artist I know LOVES commissions. Commissioning a painting give us artists the chance to create something different. Most of what I paint is what I know will sell here in my art gallery in Asheville: Blue Ridge Mountain landscapes, trees in various seasons, local waterfalls, i.e. things that people purchase to remind them of their vacation in Asheville, North Carolina. However, I've been commissioned to paint a Venice, Italy canal, the Canadian Rocky Mountains, a seaport town at sunset in New Zealand, the Alps, and a shrimp boat on a coastal river just to name a few. A couple just came into my art studio yesterday and showed me a really beautiful photo of the view off their back deck and asked, "Can you paint that?" Yep. :)

If you absolutely love doing what you do, then commissioning a painting is fodder for previously unplanned for joy!

The result of a client commissioning a painting is that I'm often entertained and challenged by some new idea I'd not thought of painting before, or I can enjoy painting something (like the Canadian Rocky mountains) that would take a long time to sell here in Asheville where people are mostly looking for Appalachain scenes. Bottom line is that commissions and artists have a long history and that's part of how we stay in business. And if you absolutely love doing what you do (and I do!), then commissioning a painting is fodder for previously unplanned for joy!

That's just how I roll.

Understanding Art 101

As an artist with an open studio in Asheville, North Carolina, I am around artwork and people all day long. People from all over the country visit me, check out my paintings and sometimes chat with me. Oftentimes, we talk about the types of artwork they like and don't like and they ask a lot of questions to try to understand my specific technique. I love these conversations. I love talking about art and help people appreciate the artwork they're seeing. My passion is that people at least appreciate (if not enjoy) all the artwork they see, whether it's from the ancient Greeks, Renaissance masters or modern abstract.

Recently, I was having a conversation with a studio visitor about different art styles and artistic periods and he admitted that he did not understand most art at all. That conversation got me thinking, and because of that, I decided to write a blog series based on a lecture I've given several times on the subject of "understanding art" because I think that's important. Understanding art does not mean you have to enjoy it or like the art at all. Understanding the art involves understanding the world view of the artist. This is crucial because knowing the world view of a person (their comprehensive conception of the world) helps us interpret what that persons says and does.

So, for the next few weeks, I'm going to talk about chronological periods of world views and how those views affected the arts and culture. The world views I will cover include theism, deism, naturalism, nihilism, existentialism, modernism, new-age pantheism, and post-modernism. Sound exciting? Maybe I'm a geek but I think it's fascinating! Knowing a bit about these world views and knowing where a person is coming from helps us to better appreciate and understand that person. Who doesn't want to do a better job of that?

Half Baked Ideas...

I usually don't show anyone what a half-completed painting looks like, but then I thought it might actually be interesting for friends to see. Every painting I do goes through what I call "the ugly stage" and these pieces, each approximately 50% complete, have JUST come out the other side of that ugly stage. Admittedly, they ain't beauties yet but they're not as hideous looking as they were a few days ago (trust me on that). When these pieces are complete, I'll post side-by-side photos (in process / finished) if people are interested.

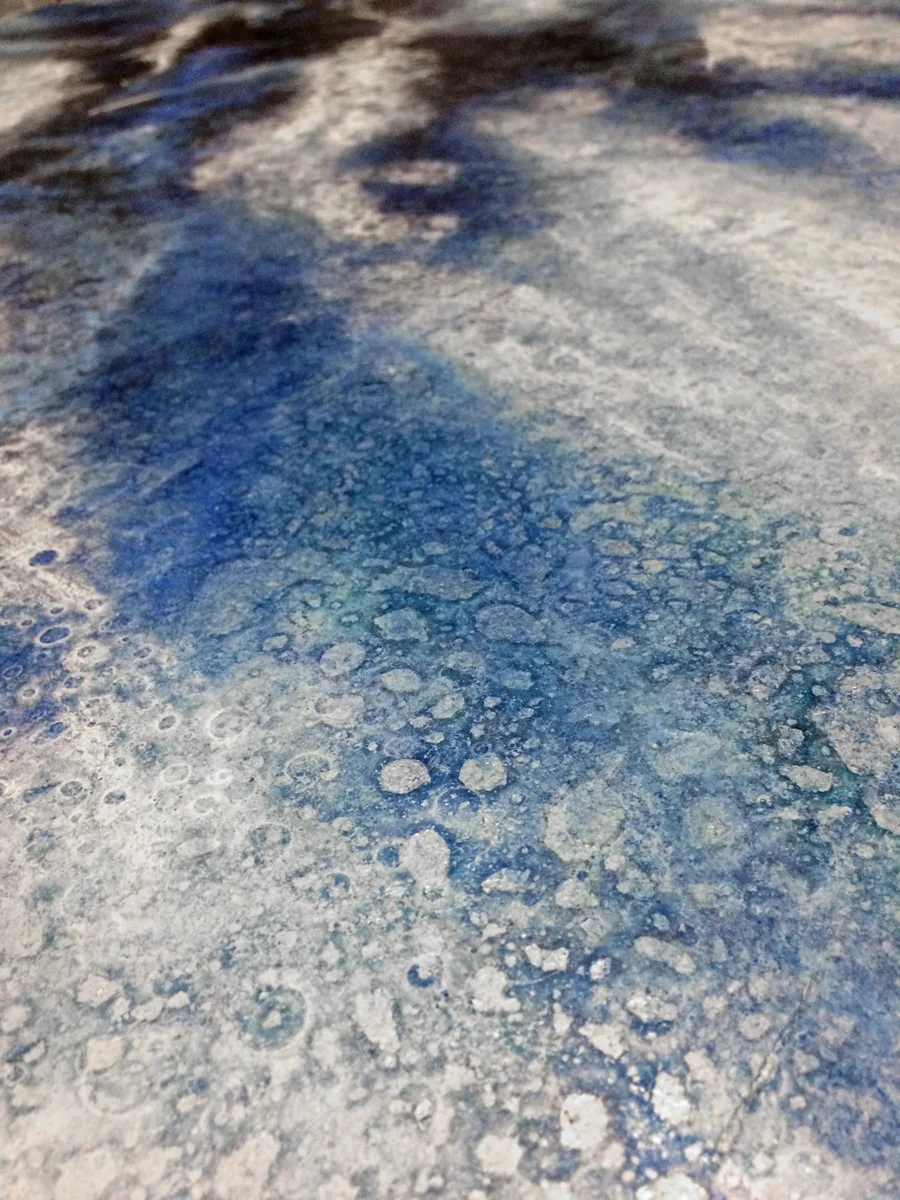

Color Explosion

The thing I really enjoy about a abstract wall art is that it feels as though I have very little control over the thing. It really does feel like it has a mind of it's own. This piece (above) is a studio photo of what is the largest abstract oil painting I've done. I was given several photos of the room in which it will eventually hang, and then my task was to design an abstract painting that complimented that space and would be a real statement piece. So I had an idea of the colors I was going to use, but that's all.

As I began several weeks ago, I felt like I had some good "movement" going on with the texture I applied. When that texture was done and covered with metallic leaf, then I began the actual paint application, and that's when the fun starts. I just almost randomly chose the first color and a large paint brush and dove right in. What I've learned is that I really need to apply one color at a time to my paintings and let those colors dry before I apply the next layer. This takes days and days, but slowly the piece begins developing into something interesting. Then, it's a matter of looking critically at the piece and determine what is "growing" that you want to develop and accentuate, and what might need to be minimized (visual dead ends). It's kind of like working in a garden -- mulching the plants and pulling the weeds until everything you want growing is mature and beautiful and everything that should not be there is gone.

This painting is headed out to it's new home in Knoxville, TN in a couple weeks (after it gets the resin application).

Of Ruination and Rescue

I'm going to be rather vulnerable here. There's a big part of me that would like to create the impression that as an artist, I always know what I'm doing, but that wouldn't really be true. Most of the time, I do feel very confident with what I paint but then there are times that make me realize I have so much yet to learn. This week, I almost ruined a 4' x 5' painting.

The oil painting in question is a very large abstract, and as I've explained in past blogs, I am never in complete control of an abstract painting. They really do have a mind of their own. Well, it turns out this painting had self-destructive tendencies I had to deal with. I had thought I was about half done with paint application and I kind of liked where it was going and was having fun working on it. Then two days ago, I was applying paint, a little here, a lot over there, more paint here, scrape off some there, and eventually I stood back and realized I'd just completely ruined the piece. So I was going to let it all dry and then re-cover it all with aluminum leaf and start all over again.

I felt like God just before the flood, regretting even making this monstrosity. I was ready for the 40 days and 40 nights of deluge and looking forward (though rather defeated feeling) to starting over.

That's when Joy stepped to the back of my studio and took a look at it. "Oh, that's really bad," she whispered. (She's honest like that.) And I said I was going to have to start all over. Then she suggested just wiping off all the paint I had just applied that day and then taking a look at it the next day with fresh eyes. So I did, and something really weird happened. When I wiped off the fresh paint, a little paint film still stuck to the rest of the piece; a fog of blues, greens and whites. Hmmmm. Interesting. That slight film I was unable to remove completely softened the whole thing and brought everything together.

The next morning I came in and was not repulsed (always a good sign) and was able to completely save the piece. Whew.

There is a lesson here I think.

How I decide what to paint...

Today is Tuesday (my day off from painting). By the way, if you're a visitor to Asheville and roaming around the River Arts District, looking for open art studios, never fear. My studio is open and being watched by Ruth Vann, a dear friend of Joy's and mine. So as I was saying, today is my day off and I thought I would spend some time on the computer hunting for photos that inspire me (I am constantly on the look-out for a photo or an idea that would lead to a compelling oil painting).

But...what makes a "compelling" oil painting? Glad you asked, but that's a tough question to answer! When you go to Google images for instance and type in "compelling landscape photos", you get some very nice photography. But I can literally spend an hour looking at hundreds and hundreds of beautiful photos and not one of them would make a really great oil painting. Why is that?

One sticking point that causes most photos to be disregarded is that I'm looking for a subject matter (for the most part) that is either generic or is specific to Western North Carolina. That is because I have found it difficult to sell artwork that is obviously a scene from somewhere else in the country. About three years ago, I came up with what I thought was a really great idea: to paint the iconic scenes from around the whole country. My thought was that people come into my art studio from all over the country so...why just stick to local North Carolina landscape scenes? Well, that year I had a blast painting Mt. Rainier, Yosemite Valley, the plains of Nebraska, the coast of Maine and the bayous of Louisiana. I loved it. This country is huge and so incredibly scenic. Great idea, huh?

Well no. I still have a few of those paintings left. I learned something that year though. Most of my paintings I sell in my studio are to people visiting Asheville, and they're looking for something to take home to remind them of their time in Western North Carolina (not a lighthouse on the coast of Maine). So now, that's the first thing I look for: something specific to North Carolina mountains and woods, or something generic (mountains, trees, lakes, rivers etc. that could be anywhere).

But then the second thing I look for in a photo I use for inspiring a painting is whether or not it "draws you in". That is what I am looking for and I'm not really sure what does that. Lighting? Colors? Contrast? All the above? Something else? Basically, I want each painting to speak to the viewer : "come home". That's it. It's that simple. Come home. We strive and work and stress-out and play and vacation so that we can re-create Eden. We really do. I don't care what religion you are, I think that's what we're all doing. We long for paradise and try hard to create. I can't create paradise, but I can let the viewer look at it. And I like that. I believe that hints at hope. This very easily turns into a philosophical and spiritual conversation, and I won't do that here but...that really does explain what I'm trying to do with my artwork and what I'm inspired by.

"What makes this painting so sparkly?"

Questions, questions...

I'm asked by a lot of people why I paint local North Carolina landscapes (usually mountains, lakes, rivers and trees) on aluminum leaf, and I explain (at least daily) that it's because aluminum leaf reflects light. Painting on aluminum leaf, I can create a painting that is back-lit. This greatly intensifies the color. How I came up with that is, well, the fault of a French architect in 1163.

When I was twenty years old, a friend of mine backpacked through Europe with me and during those travels (every American twenty year old should do this trip by the way) we found Paris, and the highlight was Notre-Dame Cathedral.

I was quite surprised to see how large the cathedral actually was. It is hulking and awesome. Honestly, I didn’t know much about the Notre-Dame apart from the Hunchback that made the place famous.

One side of the cathedral was lined with cafes for people queuing up to go in the church. Interestingly, the chairs of the restaurants were almost all facing outside. I thought it was strange as I would probably prefer to face in towards whoever I was with. If I was alone, I would not face outside, I don’t like strangers in the queue watching me eat.

We got there during Mass ("hey, don't mind us Presbyterians --carry on, carry on"). It was magical. So utterly beautiful. And when Mass was done, I turned to leave and then I saw it: the rose window. Oh my gosh. I'd never seen color do what it was doing as the sun penetrated the colored glass. I remember thinking, "How can I get PAINT to do that?" At the time, this seemed like a ridiculous question because you paint on a canvas and how do you shine light through a canvas, right?

This idea went no where for many years until I saw the Orthodox church answer to stained glass windows: ICONS. Icons are painted on gold. P-A-I-N-T-E-D on gold. Well, I couldn't afford gold so I found aluminum leaf and a new genre of art was born, from a rose window in Paris and a Madonna and child on gold. You never know where a creative muse will lead you. You just follow it and see!

What is 'good' art?

There are different answers to that question, which doesn’t surprise me. What does surprise me is that even asking the question scandalizes some people. I’ve heard folks say things like, “there’s no such thing as good art or bad art. Art comes from inside the soul. How can you judge that?” So before I even begin to take a stab at answering the question “what is good art?” Let me first defend the right to ask the question in the first place.

You Can Judge Art??

To begin with, let me say that yes, it’s completely improper to criticize the self-expressive art of a six-year-old. A six-year-old cannot produce good or bad art. To a parent, it’s all beautiful. It can’t be judged. The same could be said for someone who enjoys dabbling in watercolor or oil paint for fun or self-expression. Painting, sculpting, practicing the piano… is all fun and personally, I would encourage anyone to explore their creativity—society would be healthier for it. But not all art is like that. The art of a college student earning his painting degree should be judged and analyzed. The work of a professional artist is judged all the time, and rightly so, because he has submitted it to the public eye, not simply as self-expression, but as true art—as expression of something transcendent. If you handed me a page from your diary, it would be completely inane for me to redline a spelling error. On the other hand, if I were a creative writing instructor and you were my student, it would be kosher for me to mark up your essay. Indeed, I would be a poor teacher if I did not, even if it were a good essay. So whether we can judge art is entirely dependent on our context. In the right context, we are free to make certain judgments. In fact, we judge all the time, and that’s not inherently problematic. Does everyone sing equally well? Are all poets equally skilled? If you have a favorite restaurant or a favorite beer or favorite movie or a favorite band or a favorite anything, you’re judging—you’re praising something as superior to something else, or to everything else. We judge, and that’s simply the truth. Some things are better than other things, and it is inconsistent, even dishonest, to pretend otherwise. So can we judge art? We do, whether we think we can or not. What we need most, then, is to critique and analyze our criteria. The criteria which we use to judge between good and poor art will be the subject of my next few posts.

"The Rules" of Art

Art: The Process of Creating an Oil Painting

I recall an episode of Downton Abby where a certain gentleman made a glaring fashion blunder by wearing a white tuxedo vest. Obviously, he should have known better—should have known to wear the black vest. The family was scandalized and horribly embarrassed for him. I can only imagine.

Rules that dictate behavior in “high society” are often comical, and it’s easy to question their validity at all. Aren’t norms arbitrary and man-made? If society banded together, we could all just as well decide that it’s proper to wear orange vests to our dinner parties, and then that would be the right choice, right? The truth is, some rules are like that. And some aren’t. Some rules are really more conventions than rules. But the rules I want to proceed to discuss here – the rules of art, are far from arbitrary or man-made. We artists take our cue from nature itself. Nature – the way things work, the way things are put together – is what dictates the standards for beauty. I’d like you to study this photo:

This is a oil painting by John William Waterhouse entitled “The Lady of Shalott”. Look at the painting and notice where your eyes are led and where they rest. Are you haplessly scanning the piece, with nowhere for your eyes to land? Probably not. If you’re like most people, your eyes will immediately fall on the face, and then wander to the golden prow of the boat, and then follow the gentle curve of said boat, up the figure to rest once again at the girl's face. Your eye does this for a reason. The painter, John William Waterhouse, used a device called the Golden Section when he composed this piece. The Golden Section (also known as the Golden Ratio or the Divine Proportion) is an almost magical ratio. Mathematically, it is the ratio 62:38. This ratio is found all over nature, all over art, all over everything we deem beautiful. The Golden Section is the most aesthetically pleasing division of space. Looking up at the above photo again, start at the right side and trace your eyes over 62% of the way to the left. That point corresponds to the placement of the woman’s face. Start from the bottom of the photo and measure out 62% and you’ll find your eyes again stop at the woman’s face. Your eyes naturally fall on her because they are carried there by this intersection of two very important mathematical divisions. But there is another reason your eyes are drawn to rest upon the woman’s head. Waterhouse employed not only the Golden Section in the composition of his piece but also his knowledge of contrast. Your eye will always travel to where the lightest light and the darkest dark meet. There is a reason the Lady is wearing white and the sun is shining bright on the top of her head: this creates the point of greatest contrast in the painting against the dark background of the trees. The result is that your eyes are not scrambling but resting naturally at the exact point the artist predetermined to draw them. I might also mention the use of complementary colors in this painting. Complementary colors are opposites on the color wheel and a complementary color is used to either balance the predominate color or to accent it. Look at the painting again. The predominant colors in this piece are muted greens but he also uses the complement of muted reds. In the water we see blues and violets and that is complemented with the golds and yellows. All this to say: this painting was not haphazardly assembled. Waterhouse worked within The Rules and created a masterpiece.

...Good art is that it is always created with skill

The last thing I’ll say about good art is that it is always created with skill. There should be somewhat of a mystery about it. When standing in front of a beautifully painted piece of art you should be prompted to awe and wonder, asking the question, “how did he or she do that?” To be honest, much of the artwork in modern times leaves me asking no such question. There is no mystery and no obvious skill. Such art neither commands my respect nor holds my interest. Art that will be remembered throughout history is not that which ignores the rules, nor that which becomes tirelessly bogged down with the rules. No, art that lasts will be that which so internalizes the rules that it moves beyond them, synthesizing and remixing them into new focal points of beauty—new reinventions of that created order which was there from the beginning, but which is inexhaustible in its number of true expressions.

To School or Not to School...

School of Art

Now and then, I am asked by aspiring young artists if I have any recommendations for an art school to learn to paint landscape or abstract art. The answer to that question is always quite difficult…

…If a person is gifted creatively, a fine arts major could be extremely beneficial, or it could destroy their potential. It depends on who they are, how they’re wired, and what they’re looking for. One would think that the goal of a fine arts degree would be to learn all the necessary tools for making a living as an artist, right? This would seem like a realistic expectation given the tens of thousands of dollars mommy and daddy are spending for the degree. I mean really, why spend all that time and effort and money just to graduate and flip burgers at McDonalds? (or rather, flip burgers while paying interest on a $60,000 student loan). But this happens all the time, and it’s rarely for a lack of talent.

An option I think everyone would do well to consider is to look for an accomplished artist and ask them to mentor you. Then, go to school and learn something that would help you as an artist (like marketing or business) and all along, learn your craft from your mentor. This is how they did it back in the day and may make a whole lot of sense to bring back.

But if you're dead set on going to art school, here are my suggestions:

First of all...

First, get online and take a look at artwork of the actual art students. That will tell you a lot. You might think the artwork looks really cool, but the question you need to ask yourself is: does this artwork look like anything anyone would actually purchase and put in there home? I know… I know… even asking that question will insult some aspiring artists, but more than likely I’m saving them from a lifetime of burger flipping. Now, if all you want to do is visually express yourself and you don’t give a wit about making a living actually doing art, then none of this applies to you. The people I’m writing to are those who want to be trained to make a living by learning a skill. For that to happen, you need to learn to make work that others value. Makes sense, right? It’s not rocket science.

Then...

Once you find a school that looks promising, call that school and schedule a tour. A lot of schools will even allow you to sit in on a class, which can be extraordinarily helpful. You’ll be able to tell right away whether the instructors are training students in a new skill or just touting “unconfined expression”. If they are doing the latter, their whole venture is self-refuting—they are building their program on the false premise that art isn't a skill, but if that were truly the case, you wouldn’t need to go to school for it in the first place.

IN CLOSING...

The most important thing to stress is that all of us would do well with input, advice and encouragement from someone who does what we want to do better than we do it (whether we're talking brain surgeons, journalists, actors, dentists or artists). Get input and encouragement. And if you try to do that at an art school, choose carefully. The right school can be a really great find (and the wrong one will be a waste of countless thousands of dollars).

Blog Archive

-

2025

- Oct 28, 2025 What can I learn from Makoto Fujimura in 2025? Oct 28, 2025

- Oct 12, 2025 What can I learn from Pablo Picasso in 2025? Oct 12, 2025

- Oct 10, 2025 What can I learn from Raphael in 2025? Oct 10, 2025

- Oct 8, 2025 What can I learn from Georgia O’Keefe in 2025? Oct 8, 2025

- Sep 28, 2025 What can I learn from Caravaggio in 2025? Sep 28, 2025

- Jul 25, 2025 What can I learn from Thomas Gainsborough in 2025? Jul 25, 2025

- Jul 20, 2025 What can I learn from Leonardo da Vinci in 2025? Jul 20, 2025

- Jul 15, 2025 What can I learn from Michelangelo in 2025? Jul 15, 2025

- Jul 2, 2025 What can I learn from Van Gogh in 2025? Jul 2, 2025

- Jun 25, 2025 What can I learn from Renoir in 2025? Jun 25, 2025

- Jun 23, 2025 What can I learn from Claude Monet in 2025? Jun 23, 2025

- Jun 21, 2025 Using Complimentary Colors for Shading Jun 21, 2025

- Jun 17, 2025 How and When to use Complimentary Colors Jun 17, 2025

- May 30, 2025 Perspective in Art 101: How to Make Your Drawings Pop Off the Page May 30, 2025

- May 26, 2025 How to Really Understand Medieval Art May 26, 2025

- May 22, 2025 Staying Creative May 22, 2025

- May 10, 2025 AT Experience May 10, 2025

- May 3, 2025 Go Take a Walk! May 3, 2025

- Apr 25, 2025 Periods of Art: Mannerism Apr 25, 2025

- Apr 17, 2025 Finding Meaning in the Abstract: Pointers for Understanding Modern Art Apr 17, 2025

- Apr 16, 2025 The Quiet Labor Apr 16, 2025

- Apr 12, 2025 To Art: a Poem Apr 12, 2025

- Apr 5, 2025 The Enchantment of Art Nouveau Apr 5, 2025

- Mar 23, 2025 "What was it like going to art school?" Mar 23, 2025

- Mar 18, 2025 Why I Love the Rococo Period Mar 18, 2025

- Mar 4, 2025 Expressing Joy Through Art Mar 4, 2025

- Feb 28, 2025 The Connection Between Art and Frustration Feb 28, 2025

- Feb 23, 2025 Neoclassicism: Bringing Ancient Style Back to Life Feb 23, 2025

- Feb 18, 2025 On my walk Feb 18, 2025

- Feb 12, 2025 Art at the Very Beginning Feb 12, 2025

- Feb 10, 2025 Monet and Renoir: A Personal Reflection on Their Differences Feb 10, 2025

- Feb 6, 2025 The Fount of Creation: A poem Feb 6, 2025

- Feb 1, 2025 The Connection Between Art and Grief Feb 1, 2025

- Jan 29, 2025 A Journey Through Medieval Art: Stories from the Middle Ages Jan 29, 2025

- Jan 26, 2025 The Story of Art: The Romantic Period Jan 26, 2025

- Jan 16, 2025 The Relationship Between Music and Painting Jan 16, 2025

- Jan 12, 2025 Periods of Art: Baroque Jan 12, 2025

- Jan 11, 2025 Marketing your Artwork Jan 11, 2025

- Jan 7, 2025 Exploring the Golden Ratio in Art Jan 7, 2025

- Jan 3, 2025 Artistic Enlightenment: Lessons from Italy Jan 3, 2025

-

2024

- Dec 29, 2024 Why Travel is Crucial for Unleashing Creativity Dec 29, 2024

- Dec 22, 2024 Steps to Becoming a Full-Time Professional Artist Dec 22, 2024

- Dec 10, 2024 How to Determine Subject Matter for Your Next Painting Dec 10, 2024

- Dec 3, 2024 My Favorite Artist Dec 3, 2024

- Dec 1, 2024 Creativity and Exploration Dec 1, 2024

- Nov 13, 2024 Impressionistic Heroes of Mine Nov 13, 2024

- Nov 10, 2024 "So how do you DO this?" Nov 10, 2024

- Nov 3, 2024 Discovering the Bond Between Nature and Art Nov 3, 2024

- Nov 1, 2024 How Art Can Help Us Cope with Stress Nov 1, 2024

- Oct 27, 2024 How to Select the Perfect Art for Your Home Oct 27, 2024

- Oct 24, 2024 What to Do When You Feel Like Giving Up as an Artist Oct 24, 2024

- Oct 14, 2024 Book Review: The Artist’s Way Oct 14, 2024

- Oct 11, 2024 How to find Inspiration for your art Oct 11, 2024

- Sep 24, 2024 Crafting the Perfect Title for Your Artwork Sep 24, 2024

- Sep 14, 2024 The Worst Advice I’ve Ever Received as an Artist Sep 14, 2024

- Sep 8, 2024 Overcoming Artist’s Block: Practical Tips Sep 8, 2024

- Aug 30, 2024 Exploring Lessons from Vincent van Gogh Aug 30, 2024

- Aug 29, 2024 Why Purchase Original Artwork? Aug 29, 2024

- Aug 25, 2024 How do you determine the best size artwork to purchase? Aug 25, 2024

- Aug 15, 2024 "So, what's this painting worth?" Aug 15, 2024

- Aug 9, 2024 What color art would go best in my home? Aug 9, 2024

- Aug 4, 2024 How to deal with criticism as an artist Aug 4, 2024

- Mar 27, 2024 Question 12: "What do you do when you have a mental block?" Mar 27, 2024

- Mar 27, 2024 New Goals + Winter Months = "Outside the Box" Creativity Mar 27, 2024

- Jan 8, 2024 Question 11: Where do you get inspiration for your work? Jan 8, 2024

-

2023

- Sep 11, 2023 Question 10: "Do you have your work in galleries?" Sep 11, 2023

- Aug 27, 2023 Question 9: "How do you manage the business side of your art business?" Aug 27, 2023

- Aug 20, 2023 Question 8: "Do you advertise?" Aug 20, 2023

- Aug 13, 2023 Question 7: "How do you price your work?" Aug 13, 2023

- Jul 30, 2023 Question 6: "What are the positive points and negative points about having an 'open studio'?" Jul 30, 2023

- Jul 19, 2023 Question 5: "Would you mind critiquing my work at some point?" Jul 19, 2023

- Jul 1, 2023 Question 4: "Would you recommend art school, and if so, how would you find the right one?" Jul 1, 2023

- Jun 24, 2023 Question 3: "Did you go to art school? If so, where?" Jun 24, 2023

- Jun 16, 2023 Question 2: "How long have you been selling your work professionally?" Jun 16, 2023

- Jun 10, 2023 Question 1..."How long have you been an artist?" Jun 10, 2023

- Jun 4, 2023 So, you're thinking about art as a career? Jun 4, 2023

- Mar 3, 2023 "What inspires you as an artist?" Mar 3, 2023

- Feb 15, 2023 Should I buy a completed painting OR commission a painting? Feb 15, 2023

- Jan 23, 2023 "How do you Price Your Work?" Jan 23, 2023

-

2022

- Dec 1, 2022 An Artist in Italy (Part 3) Dec 1, 2022

- Nov 16, 2022 An Artist in Italy (Part 2) Nov 16, 2022

- Nov 8, 2022 An Artist in Italy (Part 1) Nov 8, 2022

- Oct 10, 2022 When Remodeling a Home... Oct 10, 2022

- Aug 22, 2022 How to Handle Failure Aug 22, 2022

- Jun 3, 2022 "What is it like being an artist these days?" Jun 3, 2022

- May 21, 2022 "Are All Artists Introverts?" May 21, 2022

- May 9, 2022 What Makes a Painting a Good Piece of Art? May 9, 2022

- Apr 1, 2022 The Story Behind…"Gentle Showers on a Summer Afternoon" Apr 1, 2022

- Mar 19, 2022 The Story Behind..."Blue Ridge Summer Afternoon" Mar 19, 2022

- Feb 18, 2022 Your Opinion Please... Feb 18, 2022

- Jan 22, 2022 What's in a Compliment? Jan 22, 2022

-

2021

- Dec 25, 2021 My Christmas Present to Joy Dec 25, 2021

- Dec 12, 2021 Deep in the Heart Dec 12, 2021

- Nov 29, 2021 "How do you know you're done with a painting?" Nov 29, 2021

- Nov 1, 2021 Does it Matter What Other People Think of My Art? Nov 1, 2021

- Oct 12, 2021 Creatively Inhaling... Oct 12, 2021

- Aug 31, 2021 More Fun than I Know What to do With Aug 31, 2021

- Aug 13, 2021 “Are You Self Taught?” Aug 13, 2021

- Jul 21, 2021 New Art Gallery on the West Coast Jul 21, 2021

- Jun 23, 2021 "Art from the Heart" vs "Commissioned Art" Jun 23, 2021

- May 28, 2021 More Questions and Answers May 28, 2021

- May 17, 2021 What does Diversity have to do with honest artwork? May 17, 2021

- May 4, 2021 More Questions and Answers May 4, 2021

- Apr 30, 2021 Questions and Answers Apr 30, 2021

- Apr 16, 2021 And the Next Blog Post is... Apr 16, 2021

- Mar 10, 2021 How do you create when you don't feel like creating? Mar 10, 2021

- Feb 11, 2021 "Mullaghmore": The Story Behind the Painting Feb 11, 2021

- Jan 28, 2021 A Look Back to "The Dark Year" Jan 28, 2021

- Jan 17, 2021 Studio Expansion...Hello Northeast! Jan 17, 2021

- Jan 7, 2021 How to Create the Perfect Painting Jan 7, 2021

-

2020

- Dec 1, 2020 A personal answer to a personal question... Dec 1, 2020

- Nov 4, 2020 Using Art to Express my Politics Nov 4, 2020

- Oct 16, 2020 Sometimes, just "having fun" is a good enough reason Oct 16, 2020

- Oct 4, 2020 The Best Painting Delivery Ever... Oct 4, 2020

- Sep 7, 2020 How a Dinky Little Virus Changed my Art Business Sep 7, 2020

- Aug 9, 2020 Adaptation: Survival of the Most Flexible Aug 9, 2020

- Aug 3, 2020 Story Behind the Painting: "Sundown over the Blue Ridge" Aug 3, 2020

- Jul 18, 2020 Cure for Covid blues Jul 18, 2020

- Jul 5, 2020 Where Does it Take You? Jul 5, 2020

- Jun 3, 2020 Story Behind the Painting: Autumn Day on the French Broad River Jun 3, 2020

- May 24, 2020 Story Behind the Painting: Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat May 24, 2020

- Apr 30, 2020 Q&A: SESSION TWO Apr 30, 2020

- Apr 22, 2020 Q&A: SESSION ONE Apr 22, 2020

- Apr 8, 2020 What I'll Miss When This Pandemic is Over... Apr 8, 2020

- Mar 20, 2020 Entertaining Angels Unawares Mar 20, 2020

- Mar 8, 2020 In Celebration of Art Mar 8, 2020

- Feb 27, 2020 "The Bridge" Feb 27, 2020

- Feb 8, 2020 The Most Interesting Question of the Year (but it's only February so...) Feb 8, 2020

- Jan 29, 2020 "Can I Watch You?" Jan 29, 2020

- Jan 14, 2020 From Point A to Point Z Jan 14, 2020

- Jan 5, 2020 An Impractical Idea Jan 5, 2020

-

2019

- Dec 17, 2019 My Beautiful Baby on Display Dec 17, 2019

- Dec 3, 2019 Regarding the Selection of an Artistic Theme Dec 3, 2019

- Nov 20, 2019 "What's Your Best Price on This Piece?" Nov 20, 2019

- Nov 13, 2019 A Really Unique Commission Project Nov 13, 2019

- Nov 6, 2019 Fun with Art Scammers Nov 6, 2019

- Nov 3, 2019 "How did you know you wanted to be an artist?" Nov 3, 2019

- Oct 30, 2019 How do you know when a painting is "done"? Oct 30, 2019

- Oct 20, 2019 The piece I had to paint: "Côte d’Azur" Oct 20, 2019

- Oct 18, 2019 Inspiration Everywhere! Oct 18, 2019

- Aug 26, 2019 Contentment vs Restlessness Aug 26, 2019

- Aug 14, 2019 "Why Should I Purchase Artwork?" Aug 14, 2019

- Aug 11, 2019 What Was Art School Like? Aug 11, 2019

- Aug 7, 2019 "The Four Seasons on the French Broad River" Aug 7, 2019

- Jul 30, 2019 Joy Unspeakable Jul 30, 2019

- Jul 7, 2019 Of Mountains and Oceans Jul 7, 2019

- Jul 3, 2019 Lessons I've Learned as an Artist Jul 3, 2019

- Jun 26, 2019 St.Claire Art Opening at the AC Hotel, Asheville Jun 26, 2019

- Jun 23, 2019 "How do you decide what to paint?" Jun 23, 2019

- Jun 5, 2019 One of my All-Time Heroes Jun 5, 2019

- Jun 2, 2019 Regarding "Inspiration" vs "Necessity" Jun 2, 2019

- May 29, 2019 The Best Complement I've Ever Received May 29, 2019

- May 19, 2019 "What are you Working on These Days?" May 19, 2019

- May 5, 2019 "Frankenstein-ing" a painting May 5, 2019

- Apr 17, 2019 The Big Reveal Apr 17, 2019

- Apr 3, 2019 "How do you Decide What to Paint?" Apr 3, 2019

- Mar 27, 2019 "I'm just not making the sales I need!" Mar 27, 2019

- Mar 20, 2019 Making the Most of Mistakes Mar 20, 2019

- Mar 10, 2019 Exploring Austin Galleries, Part 2 Mar 10, 2019

- Feb 25, 2019 Exploring Austin Galleries, Part 1 Feb 25, 2019

- Feb 10, 2019 Progress! Feb 10, 2019

- Jan 23, 2019 Preliminary Photos of my "Sails" Prototypes Jan 23, 2019

- Jan 16, 2019 The Benefits of Slowing Down Jan 16, 2019

- Jan 8, 2019 New Idea Taking Shape Jan 8, 2019

-

2018

- Dec 29, 2018 Looking Back and Looking Ahead Dec 29, 2018

- Dec 19, 2018 Percolating Creativity Dec 19, 2018

- Dec 16, 2018 So then... Dec 16, 2018

- Dec 12, 2018 What if... Dec 12, 2018

- Dec 5, 2018 Recent Projects on my Plate Dec 5, 2018

- Dec 3, 2018 Claude: My Creative Hero and Muse Dec 3, 2018

- Nov 22, 2018 Lessons I've Learned as an Artist Nov 22, 2018

- Nov 12, 2018 Planning for a Second Studio Location! Nov 12, 2018

- Nov 7, 2018 Steps Involved with a Painting Commission Nov 7, 2018

- Nov 4, 2018 How do you stay "balanced"? Nov 4, 2018

- Oct 28, 2018 What makes art "Art"? Oct 28, 2018

- Oct 21, 2018 "How Did You Stumble Across This Type of Artwork?" Oct 21, 2018

- Oct 17, 2018 "A Personal History" Oct 17, 2018

- Oct 14, 2018 Commission Confusion Oct 14, 2018

- Oct 10, 2018 "Aqueous Dream" Oct 10, 2018

- Oct 7, 2018 Beauty in the Center of the Pit Oct 7, 2018

- Sep 30, 2018 Only North Carolina? Sep 30, 2018

- Sep 23, 2018 The Price of Being a Landscape Painter Sep 23, 2018

- Sep 9, 2018 Thoughts on New Directions, New Possibilities Sep 9, 2018

- Aug 29, 2018 SURVEY: GLOSSY OR SATIN Aug 29, 2018

- Aug 22, 2018 Regarding Commissioning a Painting Aug 22, 2018

- Aug 19, 2018 On the Brink of a Huge Failure Aug 19, 2018

- Aug 7, 2018 "The Trail That Never Ends" Aug 7, 2018

- Aug 5, 2018 Inspration Begets Inspiration Aug 5, 2018

- Jul 19, 2018 Rejuvenating Creativity! Jul 19, 2018

- Jul 15, 2018 A Word About Accolades Jul 15, 2018

- Jul 10, 2018 Where it Began Jul 10, 2018

- Jul 4, 2018 Funny Things People Say in an Art Studio Jul 4, 2018

- Jun 29, 2018 "The Time Between Times" Jun 29, 2018

- Jun 27, 2018 World View #8: Post Modernism Jun 27, 2018

- Jun 21, 2018 World View #7: New Age Pantheism Jun 21, 2018

- Jun 12, 2018 A New Opportunity -- A New Idea Jun 12, 2018

- Jun 6, 2018 The Art of Dinner (at the Grove Park Inn) Jun 6, 2018

- Jun 3, 2018 National Geographic?!? Jun 3, 2018

- Jun 1, 2018 World View #6: Modernism Jun 1, 2018

- May 24, 2018 The Art of Dinner (with the Dallas Cowboys) May 24, 2018

- May 13, 2018 Carving Mountains from Scratch May 13, 2018

- May 10, 2018 "Trigger Warning" May 10, 2018

- May 7, 2018 World View #5: Existentialism May 7, 2018

- Apr 29, 2018 World View #4: Nihilism Apr 29, 2018

- Apr 11, 2018 World View #3: Naturalism Apr 11, 2018

- Apr 4, 2018 World View #2: Deism Apr 4, 2018

- Mar 26, 2018 World View #1: Theism Mar 26, 2018

- Mar 23, 2018 A Time to be Disturbed Mar 23, 2018

- Mar 14, 2018 Understanding Art 101 Mar 14, 2018

- Mar 8, 2018 The Organ Mountains Mar 8, 2018

- Mar 7, 2018 "Remember...there are no mistakes with art" Mar 7, 2018

- Mar 2, 2018 The Biltmore Estate Mar 2, 2018

- Feb 21, 2018 How to Make a Living as an Artist (Part 2) Feb 21, 2018

- Feb 12, 2018 How to Make a Living as an Artist Feb 12, 2018

- Feb 4, 2018 How do you create when you don't feel creative? Feb 4, 2018

- Jan 24, 2018 Gallery Representation in Hendersonville! Jan 24, 2018

- Jan 19, 2018 Metalizing the Biltmore Estate Jan 19, 2018

- Jan 15, 2018 Four Seasons on the Blue Ridge Jan 15, 2018

- Jan 11, 2018 About Ice... Jan 11, 2018

- Jan 10, 2018 What's Next? Jan 10, 2018

-

2017

- Dec 20, 2017 Mountain Top Experiences Dec 20, 2017

- Dec 18, 2017 The Power of Mystery Dec 18, 2017

- Dec 7, 2017 Forsyth Park Fountain Dec 7, 2017

- Dec 6, 2017 Angsty or Terrified? Dec 6, 2017

- Dec 4, 2017 To the "Angsty" Artist... Dec 4, 2017

- Dec 3, 2017 "I woudn't pay HALF of what he's asking!" Dec 3, 2017

- Nov 20, 2017 "On the Water" Nov 20, 2017

- Nov 19, 2017 Song of Autumn Nov 19, 2017

- Nov 15, 2017 "Top of the Mountain" Nov 15, 2017

- Nov 5, 2017 "How do you decide what to paint?" Nov 5, 2017

- Nov 2, 2017 "Valley of Shadows" Nov 2, 2017

- Nov 1, 2017 Forest of Autumn Gold Nov 1, 2017

- Oct 25, 2017 Then and Now Oct 25, 2017

- Oct 24, 2017 Catawba Falls Oct 24, 2017

- Oct 18, 2017 "Valley of Shadows" Oct 18, 2017

- Oct 11, 2017 Autumn River Song Oct 11, 2017

- Oct 3, 2017 Autumnal Shift Oct 3, 2017

- Sep 28, 2017 Mystic Summer Morning Sep 28, 2017

- Sep 24, 2017 Valley of Shadows Sep 24, 2017

- Sep 1, 2017 the breakers Sep 1, 2017

- Aug 24, 2017 When the Sun Went Dark Aug 24, 2017

- Aug 17, 2017 Secret Blog Post Aug 17, 2017

- Aug 14, 2017 Waterfalls Everywhere! Aug 14, 2017

- Aug 11, 2017 "Cullasaja Falls" Completion photo Aug 11, 2017

- Aug 8, 2017 Finishing up "My Marathon" Aug 8, 2017

- Aug 1, 2017 One of the Best Days Ever! Aug 1, 2017

- Jul 26, 2017 "Glacial Fractures in situ" Jul 26, 2017

- Jul 24, 2017 Inspiration and Rest Jul 24, 2017

- Jul 18, 2017 Half Baked Ideas... Jul 18, 2017

- Jul 13, 2017 Oaks on the Water Jul 13, 2017

- Jul 9, 2017 Challenged to the Core Jul 9, 2017

- Jul 5, 2017 Boats on the Water Jul 5, 2017

- Jun 30, 2017 Glacial Fractures Jun 30, 2017

- Jun 29, 2017 Winter in the Summer! Jun 29, 2017

- Jun 27, 2017 What's in a Compliment? Jun 27, 2017

- Jun 23, 2017 Thoughts on a Mighty Failure Jun 23, 2017

- Jun 20, 2017 Sunrise on the Mountain Jun 20, 2017

- Jun 14, 2017 The Last Sunset (is that dramatic or what?) Jun 14, 2017

- Jun 12, 2017 Sunset or Sunrise? End or Beginning? Jun 12, 2017

- Jun 9, 2017 At the End of the Day Jun 9, 2017

- Jun 8, 2017 Giverny: My Homage to the Man Jun 8, 2017

- Jun 2, 2017 A Funny Thing Happened at the Studio Today... Jun 2, 2017

- Jun 2, 2017 Sunrise, Sunset... Jun 2, 2017

- May 29, 2017 Color Explosion May 29, 2017

- May 22, 2017 My Largest Painting to Date... May 22, 2017

- May 18, 2017 What to do with 2000 visitors in an art studio... May 18, 2017

- May 9, 2017 My Creative Muse May 9, 2017

- May 3, 2017 Joys of Life May 3, 2017

- Apr 28, 2017 Regarding Art & Beauty Apr 28, 2017

- Apr 25, 2017 Getting Better Acquainted Apr 25, 2017

- Apr 23, 2017 Rainy Sunday Morning Thoughts Apr 23, 2017

- Apr 22, 2017 Personal Thoughts Apr 22, 2017

- Apr 19, 2017 Favorite Hikes (Inspiration in the Making)... Apr 19, 2017

- Apr 15, 2017 Inspiration is Everywhere (some of our favorite hiking trails) Apr 15, 2017

- Apr 9, 2017 "Where should we eat tonight?" Apr 9, 2017

- Apr 6, 2017 Who Else Should We See in the District? Apr 6, 2017

- Apr 1, 2017 Spring in Western North Carolina Apr 1, 2017

- Mar 29, 2017 "Can you really make a living here?" Mar 29, 2017

- Mar 25, 2017 Of Ruination and Rescue Mar 25, 2017

- Mar 21, 2017 How I decide what to paint... Mar 21, 2017

- Mar 18, 2017 Musings of an artist... Mar 18, 2017

- Mar 14, 2017 Winter thoughts Mar 14, 2017

- Mar 13, 2017 "What makes this painting so sparkly?" Mar 13, 2017

- Mar 10, 2017 You're From Where? Mar 10, 2017

- Mar 5, 2017 "No Boundaries" Mar 5, 2017

- Mar 3, 2017 Appalachian Trail Mar 3, 2017

- Mar 2, 2017 What is 'good' art? Mar 2, 2017

- Feb 26, 2017 A Trip to the Art Museum Feb 26, 2017

- Feb 23, 2017 "The Rules" of Art Feb 23, 2017

- Feb 15, 2017 To School or Not to School... Feb 15, 2017

- Feb 10, 2017 How Do I Start This Thing? Feb 10, 2017

- Feb 9, 2017 Rocky Mountains reflection Feb 9, 2017

- Feb 7, 2017 Getting Inspired Feb 7, 2017

- Feb 5, 2017 Inspiration for a painting... Feb 5, 2017

- Jan 31, 2017 Understanding Abstract Art Jan 31, 2017

- Jan 29, 2017 Chi Jan 29, 2017

- Jan 26, 2017 Process: Rocky Mountain Commission Jan 26, 2017

- Jan 12, 2017 "Summer Path Thru the Birch Trees" Jan 12, 2017

- Jan 9, 2017 "Daybreak" Jan 9, 2017

-

2016

- Dec 31, 2016 Revisiting a friend Dec 31, 2016

- Dec 28, 2016 The Trial Run Dec 28, 2016

- Dec 17, 2016 Asheville Channel Interview Dec 17, 2016

- Nov 28, 2016 "Big Mamma" begins to sing.... Nov 28, 2016

- Nov 22, 2016 An Experiment with Moonlight Nov 22, 2016

- Nov 17, 2016 Transfiguration Nov 17, 2016

- Nov 11, 2016 My Cluttered World Nov 11, 2016

- Oct 30, 2016 Sacred Space Oct 30, 2016

- Oct 22, 2016 Omikron (Fire & Ice) Oct 22, 2016

- Oct 19, 2016 "Do you know what you're going to paint?" Oct 19, 2016

- Oct 15, 2016 "Golden Pathway" Oct 15, 2016

- Oct 14, 2016 Flowers, Flowers Everywhere Oct 14, 2016

- Oct 13, 2016 OKC 2 ("The Bridge") Oct 13, 2016

- Oct 12, 2016 Headed west... Oct 12, 2016

- Sep 7, 2016 A Year of "Largest" Sep 7, 2016

- Aug 2, 2016 Transformation of an idea... Aug 2, 2016

- Jul 27, 2016 Beginning my "marathon" painting: Cullasaja Falls Jul 27, 2016

- Jul 18, 2016 My Marathon Jul 18, 2016

- Jul 13, 2016 Welcome! Jul 13, 2016

- Jul 11, 2016 Aegean Waters Jul 11, 2016

- Jul 2, 2016 The Red Planet Jul 2, 2016

- Jun 17, 2016 Puzzling and Playing Jun 17, 2016

- Jun 10, 2016 St.Claire Art Studio Tour Jun 10, 2016

- Jun 6, 2016 Hominy Valley Jun 6, 2016

- May 25, 2016 "The Acolytes" is installed in Georgetown, SC May 25, 2016

- May 19, 2016 "Zuma" May 19, 2016

- May 18, 2016 Fishy Art May 18, 2016

- May 13, 2016 "The Journey" May 13, 2016

- May 10, 2016 Hyatt Ridge (26" x 16") May 10, 2016

- May 5, 2016 "Broad River in October" May 5, 2016

- May 2, 2016 A Blast From the Past May 2, 2016

- Apr 22, 2016 Beginnings II Apr 22, 2016

- Apr 21, 2016 Appalachian Panorama Apr 21, 2016

- Apr 18, 2016 "How do you get the aluminum on the painting?" Apr 18, 2016

- Apr 14, 2016 Beginnings Apr 14, 2016

- Mar 24, 2016 St. Claire Art News & Updates Mar 24, 2016

- abstract

- aluminum leaf

- Appalachian Trail

- art as a career

- art business

- art career

- art career advice

- art commission

- art composition

- art creation

- art critique

- art education

- Art Gallery

- art gallery

- art history

- art inspiration

- art marketing

- art movements

- art periods

- art poetry

- art process

- art purchase

- art sales

- art school

- Art Studio

- art studio

- art studios

- Art Studios

- art technique

- artist

- Artist advice

- artist advice

- artist representation

- artisti creation

- artistic expression

- artistic inspiration

- artwork

- Artwork

- Asheville

- asheville

- Asheville art gallery

- Asheville art studio

- Asheville artist

- Asheville artists

- Autumn

- autumn

- birch

- blue

- Blue Ridge

- commission

- Commission

- complimentary colors

- contemporary art

- creative inspiration

- Creativity

- creativity

- cullasaja falls

- fine art

- golden section

- grief

- grove park inn

- Hiking

- impressionism

- inspiration

- installation art

- landscapes

- medieval art

- mountain trails

- mountains

- North Carolina

- ocean

- ocean artwork

- oil painting

- Oil paintings

- origins

- process

- Professional artist

- red

- reflection

- Renoir

- Resin art

- River

- River Arts District

- Statement peice

- studio

- summer

- sunset

- Sunset

- travel

- travel and creativity

- trees

- understanding art

- unique wall art

- water

- waterfall

- wave

- western north carolina

- Western North Carolina

- woods

- World Views